2020 sucked. It didn’t start sucking (e.g., Bong Joon-ho won big time at the Oscars in February). But it did end up sucking so much so that I’ve recently decided to boycott any reviewer, podcaster, etc. who began any sort of year-end discussion with the observation that 2020 turned out to be a great year for feature films. Because relatively speaking, it most certainly was not.

Since 1989, I’ve seen over 100 new films in the same year that they were released; but in 2020, I saw just over 60, and it turns out that the average grade I gave those films upon viewing is lower than any year in the last decade. Beyond the physical closure of cinemas, there was a good reason for this: U.S. distributors, large and small, held back the release of the most promising films (including half of my ten most anticipated of 2020). As such, I am doing a top 5 of the year in lieu of a top 10. On the plus side, I suppose, is the fact that all of these films turned out to be first or second narrative features by new directors.

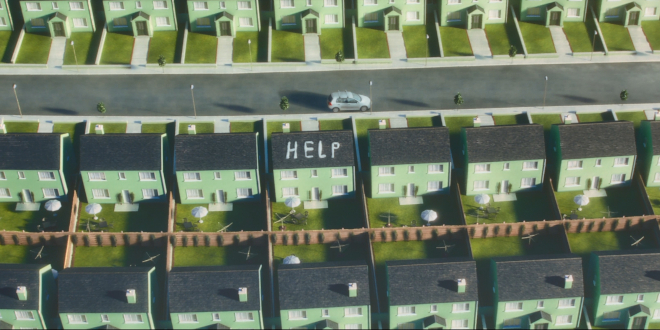

5. Vivarium. In popular film commentary, associating new releases with the claustrophobic, antisocial reality of COVID-19 lockdowns became the cliché of the year. But I submit that no other film (unintentionally) captured the moment quite like this Twilight Zone-inspired, sci-fi tale about the trappings of first-home ownership and all that follows. Unsettling from its very first moments, Imogen Poots and Jesse Eisenberg (modern indie cinema’s Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks) animate the dark comedy, while director Lorcan Finnegan adds just the right touches of surreal horror, to spawn what is, for my money, the most underrated film of the year.

4. Swallow. Swallow begins as a character study of a pregnant young wife who, physically and emotionally secluded in a prison of privilege, succumbs to an irresistible impulse to swallow inedible objects (from marbles to tacks); but the film ultimately evolves into a mini-saga of emancipation. And honestly, if that is how this had been pitched to me, I probably would have passed. But writer/director Carlo Mirabella-Davis is a sly one – unafraid to inject blunt metaphors into the visuals or bleed subtext into text, while hiding subtleties in the seemingly unsubtle (see, e.g., a reference to Revenge (2018) in a would-be nursery). And with a big assist from Haley Bennett (who I suspect may have been cast to vaguely remind us of Michelle Williams), this one earns its bold, if uneasy, catharsis.

3. Promising Young Woman. For most viewers, it seems, Promising Young Woman lives or dies on its denouement – a provocation, for sure. But for me, the second most interesting sequence of writer/director Emerald Fennell’s divisive debut involves a confrontation between our antiheroine (Carey Mulligan) and a criminal defense lawyer (Alfred Molina). I immediately thought to myself, surely that is not how this interaction ends. But among a growing crop of emerging filmmakers with a distinctly post-MeToo take on genre (in this instance, the female-driven psychodrama), Fennell manages to acknowledge the humanity of the socio-political villain du jour (the white male) far better than the likes of the indie-cinema darling du jour, Eliza Hittman, and her strained commitment to Bechdel compliance (Never Rarely Sometimes Always). The woke critics will likely criticize this aspect of Promising Young Woman for muddying the message of rape culture running rampant; but it is this sense of humanity—in both its male and female characters—that distinguishes a pointed narrative that rings true from a mere exercise in preaching to the converted.

2. Palm Springs. To someone who is not a fan of the most recent variations on the classic Groundhog Day (1993) (e.g., Edge of Tomorrow (2014), Russian Doll (2019)), Palm Springs turned out to be the most pleasant surprise—and the most rewatchable movie—of 2020. Director Max Barbakow and writer Andy Siera took a rather clever approach to riffing on that beloved film: use the audience’s familiarity to abbreviate the storytelling, without being cute with any overt references; add in another main character and adopt two perspectives; and answer some of those unanswered questions behind the original conceit without necessarily committing to a full explanation. But none of this would work as well as it does without spot-on performances – notably, Andy Samberg and Cristin Milloti (but most notably, Milloti).

1. The Assistant. To my mind, the word “systemic” has become one of the most overused adjectives – more often than not, shorthand for what is nothing more than grossly oversimplified, ideologically-motivated assumptions about the causes of social ills; an intentional hindrance to nuanced discourse. But that is not to say there are not systems that are perpetuated to benefit the few to the detriment of the many. And with this narrative feature debut, Kitty Green, already an accomplished documentarian (Ukraine is Not a Brothel (2013), Casting JonBenet (2017)), clearly knows how to bring to bear the power of nuanced cinematic storytelling to expose just how such a system works – perhaps better than any documentary could. The inquiry: how could a studio like Miramax thrive unchecked for so long under the leadership of a habitual sex offender like Harvey Weinstein? The approach: follow a highly-educated, low woman on the totem pole (Julia Garner)–assistant to a Weinstein-esque presence–through the routine tasks of one day at the office (a la Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1980 Buxelles (1975) sans the anesthetizing pacing). The dramatic centerpiece: a visit by our assistant to the head of human resources, which may have the most authentic dialogue I witnessed on screen in 2020. The net result: an empathy machine built to render the seemingly inexplicable as explicable.

Honorable mentions: Sound of Metal, First Cow