Spoiler Scale (How spoilerly is this article on a scale of 1 to 10?): 4

In recognition of the holiday, this article is the second installment of four published in February 2013 highlighting my favorite love stories put to celluloid in the 21st century.

Like a secret, In the Mood for Love is the type of film that is perhaps best shared with just one other person. However, the film is no secret to critics and cineastes around the world. Every decade, beginning in 1952, the British Film Institute publication Sight & Sound polls renowned film critics and directors from around the world requesting their top 10 “greatest” films ever made. As the number of respondents greatly expanded for the 2012 polls released last summer, the big story was how Vertigo (1958) displaced the four-decade front-runner Citizen Kane (1941) in the Critics’ Poll. But I was more interested in another development – in both polls, director Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love ranked higher than any film released in the last 20 years. (The film was tied for #24 in the Critics’ Poll and tied for #67 on the Directors’ Poll, and 42 critics and nine directors – including Paul Schrader, screenwriter of Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) – included the film on their ballot.)

In the Mood for Love is an art film in the truest sense of the word, and most of the connotations of that description apply. With virtually no script, Wong spent 15 months and two cinematographers (Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Pin Bing) capturing and conveying his own memories of 1962 Hong Kong – the setting for this story of two neighbors in a small apartments complex whose spouses are having an affair. Such indulgences do not always yield the best films; but in this case, the final results are exquisite.

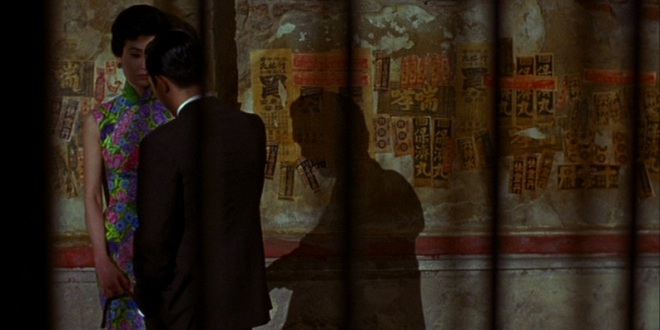

From shot to consecutive shot, there is often a distinct geometry to Wong’s composition that anticipates, illuminates, or accentuates a theme, a context, or a relationship.

And even within a single shot, the concoctions of color and texture, the movement of characters and objects, and the precision of the shallow focus are carefully combined to invoke a certain effect (for example, a moving painting).

The soundtrack is also key element. Most prominently, the same sad theme plays and replays – slowing all life down to a waltz – as if to punctuate the narrative and emotional ebbs and flows. And at the end of the film, that theme is appropriately transformed into a more transcendent piece that is only vaguely recognizable.

To be sure, the initial experience of In the Mood for Love can be frustrating to those viewers who have grown accustomed to the conventions of the 21st century erotic romance – particularly in the way the film exudes so much sensuality stripped of carnality. But in terms of bringing the viewer into the world of its two main characters, that is precisely the point. And if you fall under Wong’s spell, you will be haunted. You will be drawn in to that world again. Your understanding of, and empathy for, those characters will evolve. And with each viewing, you may take away some additional bit of truth about the delicate life cycle of love in the midst of loneliness, self-righteousness, indulgence, and guilt.

Grade: A+

![The Grandmaster [International Cut] (2013) The Grandmaster [International Cut] (2013)](http://aflixionado.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/The_Grandmaster-272x125.jpg)