Spoiler Scale (How spoilery is this article on a scale of 1 to 10?): 8

* * *

“[N]ightmares exist outside of logic, and there’s little fun to be had in explanations;

they’re antithetical to the poetry of fear.”

– Stephen King, “Why Hollywood can’t do horror,” ew.com (7/7/2008)

* * *

Writer/director David Robert Mitchell’s sophomore feature announces its genre with one of its most recognizable chestnuts – the opening kill, victimizing a character, usually female, who will often have nothing to do with the rest of the characters in film. Indeed, that genre master Wes Craven famously satirized this stake-setting trope nearly two decades ago (Scream (1996)). But as a terrified young woman (Bailey Spry, unessentially named “Annie”) bursts out of the front door of her home to the dusk of a comfy midwestern neighborhood, it becomes clear that Mitchell is bringing something else to the recipe. Our perspective is wide angle, 360 degrees – on the lookout, but with nothing to see, at least not yet. And she does not appear to be defenseless, as we hear the off camera voices of a bystander and her father asking if there is anything they can do to help. Eventually, Annie flees her car and retreats to a beach, curled up with her back to the water. She answers a mobile phone and utters a mea culpa to her father. The headlights of her car are upon her, but there is still no assailant to see. With the red illumination of the tail lights, there is only the heavy anticipation of some dreadful fate. And in the next shot on the beach the next morning, there is simply her body, mangled and deformed. There is no slashing or writhing – no violence to startle the viewer or reveal the terrible nature of the antagonist. There is only the fear and the death.

Mitchell then cuts to the world of our main character Jay (Maika Monroe), a young college student living at home, immersed in a summer malaise with her sister Kelly (Lili Sepe), the bookish Yara (Olivia Luccardi), and the first boy Jay ever kissed who has obviously never got over her, Paul (Keir Gilchrist). Jay is going on a date with a boy she likes, “Hugh” (Jake Weary), who will eventually have sex with her and reveal, in a rather unsettling manner, the curse he has inflicted upon her:

“You’re not going to believe me, but I need you to remember what I’m saying. This thing – it’s gonna follow you. Somebody gave it to me, and I passed it to you back in the car. It could look like someone you know or it could be a stranger in a crowd – whatever helps it get close to you. It could look like anyone, but there’s only one of it. Sometimes I think it looks like people you love just to hurt you …

I see it!”

“You’ll get rid of it, okay. Just sleep with someone as soon as you can. Just pass it along. If it kills you, it’ll come after me.”

And It (with all due apologies to Mr. King) does indeed follow Jay. The uninitiated (at times, the viewer) cannot see It – only the effects It has on the physical world. With the kind and generous assistance of that conventional boy next door (technically, across the street), Greg (Daniel Zovatto, bearing a canny resemblance to Johnny Depp circa 1984), Jay is able to pass the curse along, albeit only for a time, until she and her posse finally hatch a plan to dispatch of It once and for all.

_________________________

THE INEXPLICABLE NIGHTMARE

Notwithstanding Mitchell’s own characterization of his film, it appears that few critics have taken that characterization at face value; but as a piece, It Follows is indeed the very mimesis of a nightmare. To be sure, the plot never explicitly acknowledges this aspect (e.g., A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)). Nor does Mitchell tip his hat by indulging too heavily in the surreal (e.g., David Lynch).

Rather, Mitchell takes a page in part from films like Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), where the characteristics of a dream emerge from the not-quite-right facsimile of the streets of New York City. Similarly, Mitchell peppers his milieu with a number of cultural anachronisms – never allowing the viewer to anchor the film’s existence within a particular time period.

For example, the conscientious viewer, grasping for the verisimilitude of a modern theater, might ask why there is an organist accompanying a talkie.

In the same way that Kubrick would frame a textbook entitled “Introducing Sociology” within the bedroom of a prostitute as she negotiates with a potential john, Mitchell also deals in wry textual cues.

And from the very opening of the film, Mitchell draws upon the genre’s own visual history – not so much in discrete plot points as in particular images and movements.

The same could be said of the synth-heavy score by video game composer, Richard “Disasterpeace” Vreeland, which is not so much a direct emulation of Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) as a familiar approximation of that score and the numerous derivative, but less distinctive, scores from the genre entries that followed (e.g., Phantasm (1979), The Fog (1980), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)). The intended effect of all these genre touchstones is not so much imitation or genuflection as it is evocation – using those vaguely familiar elements much like the subsconcious might use to concoct the viewer’s own darkened dreamscapes.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of It Follows relies upon the undeniable, if curious, sense of reality that dreams actually impart – perhaps because the source of our reasoning, the prefrontal cortex, is usually “out to lunch”. To be sure, certain elements of the storyline seem wanting (e.g., how four bags carry enough appliances to line the edge of an olympic-plus-sized swimming pool), if not conspicuously ironic (e.g., to get into a pool, with the intent to draw the antagonist in for electrocution, during a lightning storm) – much like the machinations of our own nightmares, albeit only upon waking reflection. But Mitchell also colors the not-quite-right dream-reality with disorientingly inexplicable details – such as a tray of food in Jay’s room that appears at the beginning and the end.

As the very origin of the word “nightmare” reflects the idea of a demon haunting our minds, nowhere is that more obvious than with the film’s menace – a mutable mashup of the Shape from Halloween (1978) and Samara from The Ring (2002).

True to Hugh’s warnings, sometimes the monster looks like a person that the followed knows, which suggests various ramifications. Certainly, there is an Oedipal aspect to the final confrontation Greg and It.

And although more subtle, the last two incarnations of Jay’s also appear to be familial.

And then there is the doppelgänger of a friend, Yara, who notably approaches Jay from behind her back.

And then there is the voyeuristic angle that permeates the film – not just within particular shots (e.g., the first perspective of Jay spies on her getting in the pool from a vantage point across the street; the camera slowly approaches the open window of the car as Jay and Hugh embrace), but with the boy who appears twice peeping on Jay.

And then there is an apparition that would be familiar only to us – the only witnesses to the opening sequence – as Mitchell draws the viewer into the experience of It.

And then there are all of the strangers. Some of these strangers are seen by the followed, while some go wholly unnoticed – again, blurring the line in the viewer’s perspective between what often seems so first person, …

… and at other times, so third person – scanning, always on the lookout.

Yet attempting to ascribe any overarching meaning to It is as elusive as the science of understanding the sources and functions of nightmares or the degree to which we project our own metaphors therein. It defies any single paradigm or symbology, Freudian or Jungian. The only thing that can be said for sure is that It is – like any monster roaming our nightmares – a projection of the dreamer’s own anxiety and guilt, intertwined by the sticky threads of human contradiction. So to a middle-American girl in her late teens, It is a fear of betrayal (by family and friends alike), as well as the weight of one’s own betrayals of intimates (e.g., the passing of the curse). It is the fear of strangers and their gaze, as well as the playful acknowledgement of those stares …

… and the tinge of disappointment when they’re gone.

But even more fundamentally, It represents that most primal fear – that is, of death itself.

_________________________

SEX AND DEATH

The entry-level interpretation of It is fairly clear: the curse makes literal that which has been implied in so many kills in so many horror films.

But this STD-as-monster reading, and the more obvious moral parables to be drawn therefrom, bottoms out upon careful consideration of all of Mitchell’s conveyances.

* * *

“The action of It Follows, with its viral spread of horror and shame, could be read as an abstinence parable or a herpes nightmare or a metaphorical account of AIDS. But the point is that the It Follows’ demon is a satirical inversion of this literal case. Counter-acting the harmful or fatal effects of a sexually transmitted disease means stopping what you’re doing, not persisting. But it also means tracking down previous partners to warn them. So in this case you become the follower, and you have to be discreet about it – invisible, in fact, like the nightmarish figures in Mitchell’s movie.”

– Peter Bradshaw, “It Follows review-sexual dread fuels modern horror classic,” The Guardian (2/26/2015)

* * *

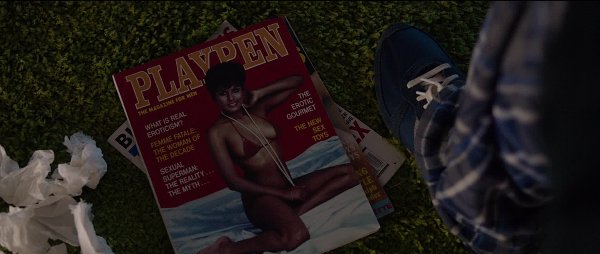

Just below that surface is essentially a coming of age story, with sex being the bridge to adulthood, and ultimately, death. On the one hand, there is a certain adolescent preoccupation with sex shared subtly among the main characters. Jay and Paul recount finding porn magazines as children in the same breath as discussing their first kiss. And the signs of that preoccupation are evident even where Hugh was hiding out from It.

On the other hand, there is an equally distinct desire in Jay to return to the safety of the womb, to wallow in the innocence of childhood shielded from mortal concerns.

But by the end of the film, that respite is breached.

And in the final confrontation with It, that water is adulterated by blood – a symbol of both sexual fertility and death.

Ultimately, that interstice between childhood and adulthood must be crossed. And from the perspective of the other side of that bridge, the characters’ view of sex has changed by the end of the film. (Post-coitus, Paul asks Jay “Do you feel different?” and Jay answers, “No.”) Preconceptions of sex, and the doors that it opens, become more complicated as the mythology of the curse reveals yet another contradiction of humanity: as the curse is contracted, sex represents a source of death (e.g., the thwarted communication of a romantic relationship, the loss of virginity, AIDS); but as it is passed along, sex becomes a reprieve from death (e.g., the emotional release, procreation).

Still, a reprieve is ultimately fleeting, and in this sense, the end brings a melancholic awakening for Jay. As Yara reads from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot in the penultimate scene, “the most terrible agony” lies not in the wounds of torture, but “in knowing for certain that within an hour, then within ten minutes, then within half a minute, now at this very instant – your soul will leave your body and you will no longer be a person, and that is certain; the worst thing is that it is certain.” (Earlier on, to similar effect, Jay’s teacher reads from T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock: “I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker, and I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker, and in short, I was afraid.”)

As alluded to by Samuel Zimmerman on the Blu Ray commentary, one theory posits that It portrays the potential harbingers of Jay’s own ultimate fate. Certainly it could be said that Jay’s first encounter of It as an impending natural death …

… is followed immediately in sequence by the victim of a rather unnatural one.

In any case, Mitchell leaves us with the reminder that death is always over our shoulder, patiently walking, biding its time.

__________________________

CROSSING THE TRACKS

Jay and her friends make three treks across 8 Mile Road into the other side of Detroit during the course of the film. In the first, Jay and Hugh do the dirty deed and introduce Jay to the curse within and without an abandoned building.

In the second, Jay and her friends track down the abandoned home where Hugh held up while he worked on passing the curse along to Jay.

And in the third, Jay and her friends walk with suitcases in hand to a deserted public pool, with Yara self-consciously pontificating, “When I was a little girl, my parents wouldn’t allow me to go south of 8 Mile, and I didn’t even know what that meant until I got a little older and I started realizing that’s where the city started and the suburbs ended, and I used to think about how shitty and weird that was.”

The weapons of their intended trap consist of all species of electronics and appliances making up the minutia of the middle-class life, which, quite ironically, It ultimately uses to literally bombard and drown Jay.

In that final confrontation, as It enters the pool area and Jay beings to fret, her friends ask her to point the invisible fiend out; and yet what Mitchell allows us to see as she points to the top of the frame is not a manifestation of It, but Old Glory …

… which continues to pop up rather conspicuously in the frame as It attacks.

And yet in the midst of all of their traversals of 8 Mile, Jay and her friends never actually interact with anyone from the other side of the tracks until (possibly) the end of the film, when Paul clearly contemplates passing down the curse.

That said, does this particular subtext fit comfortably alongside all the more psychological aspects of a film so clearly intended to approximate a nightmare? Do we really dream in terms of political and social critique? Does class guilt really make it into our subconscious?

Perhaps Mitchell bites off more than he can chew in the third act. Nonetheless, when all is said and done, Mitchell has managed to create one of the most provocative horror films of the last decade. And apropos to all of the buzz regarding plans for a sequel currently swirling in the air, it seems particularly fitting to close this essay as it began.

* * *

“Big movies demand big explanations, which are usually tiresome, and big backstories, which are usually cumbersome. If a studio is going to spend $80 or $100 million in hopes of making $300 or $400 million more, they feel a need to shove WHAT IT ALL MEANS down the audience’s throat.”

– Stephen King, “Why Hollywood can’t do horror,” ew.com (7/7/2008)

* * *

Grade: A-