Spoiler Scale (How spoilery is this article on a scale of 1 to 10?): 9

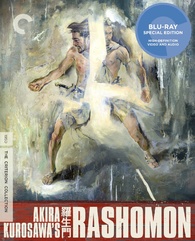

In November 2012, the Criterion Collection released the Blu-Ray edition of what is arguably director Akira Kurosawa’s most intriguing film, Rashōmon (1950), with a new digital restoration with an uncompressed monaural soundtrack, an audio commentary by Kurosawa scholar Donald Richie, a documentary with the cast and crew of Rashōmon, excerpts from a documentary on cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, an archival audio interview with actor Takashi Shimura, an interview with Robert Altman about the film, and the original and rerelease trailers, along with a booklet that includes an essay by film historian Stephen Prince, an except about the film from Kurosawa’s “Something Like an Autobiography,” and reprinted translations of the originating short stories (“Rashōmon” and “In the Grove”).

In November 2012, the Criterion Collection released the Blu-Ray edition of what is arguably director Akira Kurosawa’s most intriguing film, Rashōmon (1950), with a new digital restoration with an uncompressed monaural soundtrack, an audio commentary by Kurosawa scholar Donald Richie, a documentary with the cast and crew of Rashōmon, excerpts from a documentary on cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, an archival audio interview with actor Takashi Shimura, an interview with Robert Altman about the film, and the original and rerelease trailers, along with a booklet that includes an essay by film historian Stephen Prince, an except about the film from Kurosawa’s “Something Like an Autobiography,” and reprinted translations of the originating short stories (“Rashōmon” and “In the Grove”).

The script, representing the first of a long line of fruitful collaborations between Akira Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto (Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957)), was based on two short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa. Both stories are set in the Heian period (794-1184 A.D.), and although not explicitly referenced in the film, both are set in a time of famine and war. While the first, “Rashōmon” (1915), posed its own moral dilemma, only the setting of the framing narrative remains. “In a Grove” (1922) provided the primary plot and characters with the notable exception of the woodcutter. However, the source material is relatively sparse in terms of narrative details.

The international notoriety of the film grew with its appearance at the 1951 Venice Film Festival, where it won the Golden Lion, notwithstanding the lack of enthusiasm on the part of the producers (Dalei Motion Picture Company) and the Japanese government. From there, it gained the attention of U.S. audiences, eventually winning the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1952. And the film has confounded viewers ever since.

Kurosawa himself described the script to his skeptical producers as follows:

“Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing. The script portrays such human beings – the kind who cannot survive without lies to make them feel they are better people than they really are. It even shows this sinful need for flattering falsehood going beyond the grave – even the character who dies cannot give up his lies when he speaks to the living through a medium. Egoism is a sin the human being carries with him from birth; it is the most difficult to redeem.”

The Rashōmon Stories

The framing narrative is set at the desolate outer gate of the city – the “Rashōmon” – where a “commoner” seeks refuge from the torrential rain and finds a woodcutter and a priest sitting together in somber reflection (“I just don’t understand”). The priest introduces both the setting (12th Century Japan) and the “strange story” of a murder:

“War, earthquake, winds, fire, famine, the plague. Year after year, it’s been nothing but disasters. And bandits descend upon us every night. I’ve seen so many men getting killed like insects, but even I have never heard a story as horrible as this. … This time, I may finally lose my faith in the human soul ….”

The commoner is not particularly interested in sermons, but being a captured audience, is up for a good story. And with the priest in the background, the woodcutter begins to tell of a journey to the woods he had made three days prior.

1. The woodcutter’s testimony (as related by the woodcutter)

In a journey to collect wood from the forest in the mountains, he purports to discover a woman’s veiled hat, the cap of a samurai, a cut-up piece of rope, a shiny amulet case, and finally, the lifeless body of a man. Says the woodcutter, “I ran as fast as I could to tell the police” and “then, three days later, today, I was called to testify.” At this point, the woodcutter testifying to us – the trier of fact. In fact, all of the witnesses in the testimony scenes ask their own questions as if responding to us (“What? Did I see a sword or something? No, nothing at all.”)

2. The priest’s testimony

The woodcutter’s testimony transitions directly into that of the priest, who testifies that he passed a couple along a road in the woods thee days prior. The husband, a samurai armed with a sword and a bow and arrows, walked along side a horse upon which his wife was perched, whose face was obscured by a veil.

At this point, it is worth noting that Kurosawa wants us to see who is present for each witness’ interrogation. The woodcutter is present for the priest’s testimony, and the woodcutter and the priest are present for the testimony of the remaining parties. But by negative implication, the priest is not present for the woodcutter’s testimony.

3. The police agent’s testimony

Next, the police agent testifies that he apprehended the bandit (the notorious “Tajômaru”) two days ago at dusk along a river bank. The bandit was found writhing in pain next to a bow and several arrows strewn across the ground. The agent indicates that all of the items belonged to the dead husband. At this point, we get a taste of the spin each witness will add to their own version of the story, as the agent notes the “irony of Tajômaru being thrown off his stolen horse” as “fateful retribution.” The bandit counters that he had actually drunk from a spoiled spring earlier in the day, resulting in an “incredible stomach ache.”

4. The bandit’s testimony (as related by the woodcutter)

The bandit continues with his own testimony, beginning with the prelude, “I know sooner or later you’ll have my neck, so I’m not going to hide anything.” He admits to killing the husband three days ago. While resting on the side of the road, awoken by a fateful cool breeze that revealed the wife’s face as she passed by, the bandit made a decision right then and there:

“I thought I saw a goddess. At that moment I decided to capture her, even if I had to kill her man. But if I could have her without killing, all the better.”

And at this point, Kurosawa begins to portray the narrative of each witness on screen – consistent with traditional cinematic convention, as if the events are actually happening – with minimal narration by the witness.

In this case, the bandit chases down the couple, and after exhibiting a certain psychological instability (animalistic in his movements), he tells the husband that he has found a heap of swords and mirrors which he buried in the grove and would be willing to sell for cheap. The husband is suspicious but takes the bandit up on his offer. As they venture into the forest, the bandit points out the location of the loot, and when the husband moves ahead of the bandit, he overcomes and ties up the husband. Laughing hysterically, the bandit runs back to the brook where the wife is waiting and tells her that her husband has taken sick.

“Her face turned pale. She stared at me with frozen eyes, her expression intense like a child’s. When I saw that, I envied the man and I suddenly hated him. I wanted to show her how pathetic he looked tied to that pine tree. These thoughts that weren’t there before they filled my head.”

When they arrive at the clearing where the husband is tied up, Kurosawa provides a visual prelude to the inextricable conflict in the narrative by emphasizing each line of the triangle – not only the relationships between each party, but each relationship as seen by each party.

The wife gives chase, but after a spirited resistance, she eventually succumbs to the passions of the bandit. When the bandit finally returns to the clearing, he honorably cuts the ropes of the husband and hands him his sword. A battle ensues, whereby both men fight quite gallantly. But the bandit bests the husband, and as the husband is backed into a thicket, the bandit thrusts his sword into the husband. In the midst of the battle, the wife has disappeared, leaving the bandit to take the horse, the bow and arrows, and the husband’s sword – the latter of which the bandit attests to selling for liquor.

We now return to the Rashōmon. Keeping in mind that the stories of the priest, the police agent, and the bandit are separated by a mere screen wipe, a critical question arises at this point in the film (although the importance of the question only becomes apparent later): Who related the testimony of the bandit – the woodcutter or the priest? In his analysis of the film, Richie suggests that one cannot presume to know the answer to that question. (The Films of Akira Kurosawa (3d ed. 1996), p. 72.) But a closer viewing of the shots following the retelling of the bandit’s story suggests that Kurosawa provided us with the answer.

The first shot following the bandit’s testimony pans down from the torrential rain pounding the roof to a distant shot of the commoner, the priest, and the woodcutter.

It appears they are all sitting together, but the angle of the shot distorts the distance. In the next shot, the commoner responds to the woodcutter – relating a rumor about the bandit – as if the woodcutter had been speaking.

And in the next shot, it is revealed that the priest is actually sitting a distance away from the commoner and the woodcutter – certainly out of earshot given the noise of the rain.

Beyond the placement of the characters, Kurosawa gives us other visual clues (as discussed below). Or as Richie suggests, even if the priest heard the woodcutter re-tell the bandit’s version without complete accuracy, being who he is, the priest might not be inclined to correct the woodcutter.

In any case, the identity of the woodcutter as relator not only provides some insight as to how to interpret the over-the-top performance of the bandit, but may also reveal something about the woodcutter himself. In a story brimming with hubris and self-aggrandizement, the bandit uncharacteristically admits to the “foolish” failure to pick up the “very valuable dagger.” Why would the braggart bandit paint himself as a fool? It seems more likely that the woodcutter may be the one embellishing this particular picture, and not coincidentally, that embellishment involves the dagger.

As the conversation in the Rashōmon continues, the commoner muses, “Who knows what happened to that woman?” At this point, the priest does break in, “Well, that woman showed up at the courthouse – she was hiding in the temple when the police found her.”

Woodcutter: “It’s a lie. It’s all a lie. Tajômaru’s story and the woman’s.”

Commoner: “It’s human to lie. Most of the time we can’t even be honest with ourselves.”

Priest: “That may be. But it’s because men are weak that they lie, even to themselves.”

Commoner: “Not another sermon. I don’t care if it’s a lie, as long as it’s entertaining.”

And the priest begins to relate the testimony of the wife. Whether a reflection of his own bias or for other reasons, the priest immediately contradicts the characterization of the wife by the bandit, commenting at the outset that “she looked so docile, she was almost pitiful.”

5. The wife’s testimony (as related by the priest)

“That man in the blue kimono, after forcing me to yield to him, proudly announced that he was the infamous Tajômaru, and laughed mockingly at my husband who was tied up,” relates the wife. (NOTE: The bandit was not wearing a blue kimono.) The wife purports to express empathy for her husband – noting how horrified he must have been and how the ropes tightened the more he struggled. In her version of events, which begins after the rape, the bandit removes the husband’s ropes and runs off, laughing hysterically. (Cue the musical variation on Ravel’s “Boléro,” one of Kurosawa’s most notorious choices in the film.) She approaches her husband and embraces him, but as she looks into his eyes, there is nothing but “a cold light, a look of loathing.” She pleads with him not to be so cruel. She then runs to retrieve the dagger, cuts her husband free, and asks him to kill her. He refuses the blade, returning only a stare of disdain. At first, she recoils, begging him “don’t”; but eventually, she starts back toward him, and we are left with this image before she testifies that she fainted.

According to the wife, when she re-awoke, she saw the dagger in her husband’s chest. She left the woods, without any memory of how, and arrived at a pond, where she tried throw herself in (and “tried many different things”) to kill herself. “What should a poor, helpless woman like me do?”

We return to the Rashōmon, where the commoner notes that “women use their tears to fool everyone” including themselves. The priest goes on to relate the story of the dead husband – told through a medium – upon which the woodcutter becomes noticeably agitated.

Woodcutter: “His story was also lies.”

Priest: “But dead men don’t lie.”

Commoner: “Why is that?”

Priest: “I refuse to believe that man would be so sinful.”

Commoner: “Suit yourself. But is there anyone who’s really good? Maybe goodness is just make-believe.”

Priest: “What a frightening -“

Commoner: “Man just wants to forget the bad stuff and believe in the made-up good stuff. It’s easier that way.”

Priest: “Ridiculous -“

6. The husband’s testimony through the medium (as related by the priest)

The female medium speaks with the voice of the husband, suggesting perhaps that we are supposed to suspend our disbelief. (As the Coen brothers might suggest, accept the mystery.)

“I am in darkness now. I am suffering in the dark. Cursed be those who cast me into this dark hell.”

According to the husband, after the bandit raped the wife, he tried to woo her – saying that he only attacked her out of love, upon which the wife raises her face, as if in a trance, and replies, “take me wherever you want.” But as the bandit tried to run off with her, she stopped and plead for the bandit to kill her husband. Appalled, the bandit throws her onto the ground and asks the husband to decide her fate. (“For these words alone, I was ready to pardon his crime,” says the husband.) She manages to escape, and the bandit follows her into the woods. Hours later, the bandit returns and cuts the husband’s ropes, indicating that the wife got away (“Now I’ll have to worry about my own fate”).

Alone in the silent forest, the husband heard someone crying. (The crying could be coming from the husband himself, as his lower lip quivers; but then again, as we also learn later, the crying could be coming from the only witness – the woodcutter.) As he stumbles away from the clearing in grief, the husband retrieves the dagger and plunges it into his own heart. And at this point, Kurosawa changes the angle – focusing more clearly upon the placement of the other witnesses while the medium relates what happened next.

“Suddenly the sun went away. I was enveloped in deep silence. I lay there in the stillness. Then someone quietly approached me. That someone gently withdrew the dagger from my heart.”

We return to the Rashōmon once again to find the woodcutter pacing nervously. “It’s not true! There was no dagger. He was killed by a sword,” he exclaims, which prompts the skeptical commoner to ask, “It seems you saw the whole thing. … So why didn’t you tell the court?” “I didn’t want to get involved,” responds the woodcutter. (Note, from above, that the priest was not present in the court for the original testimony of the woodcutter.)

7. The woodcutter’s story revised

The woodcutter admits that he found the hat in the woods, as he originally related, but about 20 yards further on, he also heard a woman crying. He hid behind a bush, where he saw the bandit on his knees begging the woman to be his wife – even to the point of giving up thievery, drawing upon his savings, and making a legitimate living. “If you say no, I have no choice but to kill you.” She finally pops up, her face blank, “It’s impossible – how could I, a woman, say anything?” She runs and grabs the dagger and cuts her husband’s ropes, upon which she falls down crying between the two men. The bandit interprets her gesture as leaving her fate for the men decide. But the husband implores the bandit, “I refuse to risk my life for such a woman.” The wife looks up in shock at her husband. The husband dismisses her with disgust (“You’ve been with two men. Why don’t you kill yourself?”) and tells the bandit, “I don’t want this shameless whore, you can have her.” The bandit wipes his face of sweat and begins to leave, while the woman tries to stop him by breaking down. As the husband dismisses her (“Stop crying. It’s not going to work anymore”), the bandit takes offense (“Stop it. Don’t bully her. Women are weak by nature.”) With this exchange, the wife’s crying turns to hysterical laughter, as she sees her opportunity to exploit the male ego: “If you are my husband, why don’t you kill this man? Then you can tell me to kill myself. That’s a real man.” And to the bandit:

“You’re not a real man either. When I heard you were Tajômaru, I stopped crying. I was sick of this tiresome daily farce. I thought, ‘Tajômaru might get me out of this. If he’d only save me, I’d do anything for him.’ I thought to myself [spits on him]. But you were just as petty as my husband. Just remember: A woman loves a man who loves passionately. A man has to make a woman his by his sword.”

The husband and the bandit each draw their swords, as the wife’s mischievous smile evolves into a mocking laughter before finally morphing into a look of horror. The two men face off fearfully. They trip. They fall. They even throw dirt at each other. The husband eventually gets his sword caught in a stump, upon which the bandit backs him into the thicket and hurls his sword into the husband like a spear.

At this point, we have both a narrative convergence (the means of the husband’s death) and a visual connection between the (purported) testimony of the bandit and the revised story of the woodcutter. Within a film with shots so carefully constructed – with Kurosawa so cognizant of light, shadow, and geometry – we expect to see this obscured viewpoint of the woodcutter in telling his own version of events.

But a careful viewer would notice that we have seen this distinctly muddled, voyueristic perspective before. Although conspicuously absent from sequences relating the testimony of the husband or the wife, this shot is included in the testimony of the bandit:

At this point, there is little doubt that the bandit’s version of events has also been affected by the woodcutter’s own skewed perspective in the retelling. And with the priest sitting back at a distance as the woodcutter related the testimony of the bandit to the commoner (see above), the priest might not have been in a position to correct the woodcutter’s characterizations. In any case, unlike the priest, we already know that the woodcutter is a liar.

As the scene concludes, the bandit returns to the wife and touches her, but she recoils in repulsion and runs away. The bandit gives chase but falls to the ground in exhaustion. Eventually, the bandit retrieves both swords and vacates the scene.

Back at the Rashōmon, the commoner mocks the woodcutter (“So that’s the real story!”) to the latter’s protestations.

Priest: “It’s horrifying. If men don’t trust each other, this earth might as well be hell.”

Commoner: “That’s right. This world is hell.”

Priest: “No, I believe in man. I don’t want this place to be hell!”

Commoner: “Shouting doesn’t help. Think about it. Out of these three, whose story is believable?”

Woodcutter: “No idea.”

Commoner: “In the end, you cannot understand the things men do.” [Laughs]

As the commoner puts out the fire, they hear an infant’s cry in the distance. The commoner finds the source of the commotion in a corner of the building and immediately begins removing the kimono and amulet that surrounds the baby. The woodcutter rebukes him, calling him evil. The commoner retorts that the parents are the evil ones for abandoning the baby. The woodcutter counters that the parents left an amulet to protect the baby, and they must have been going through hell to have resorted to such actions. Echoing one of the original short stories that provided the source material, the commoner replies, “If you’re not selfish, you can’t survive.” The woodcutter screams out in philosophical desperation (“Everyone is dishonest!”) and chases the commoner into the pouring rain. But the commoner rebuffs the woodcutter with a factual discrepancy in his own revised story by accusing the woodcutter of stealing the valuable dagger, which appears from the woodcutter’s response to be true. The commoner exits the Rashōmon in laughter.

Time passes and the rain begins to subside. The baby begins crying in the priest’s hands. The woodcutter offers to take the baby – noting that he has six of his own and that another one would not make a difference. Says the priest, “Thanks to you, I think I can keep my faith in man.” “Don’t mention it.” And as the woodcutter walks out of the Rashōmon, the suns finally breaks through.

Perception of Reality v. Truth

“No one forgets the truth; they just get better at lying.” – Richard Yates, Revolutionary Road

When all is said and done, the husband was either murdered or committed suicide, but not both. By Kurosawa’s refusal to give any one narrative a presentational prevalence, we are left with the distinct and unsettling impression that all of the narratives are untrustworthy. Throughout the film, as viewers, we are overtly put in the position of the factual arbiter of a particular event, and by the end of the film, we become the moral arbiter of humanity itself. That is, we are not left to judge the veracity of the four primary witnesses – after all, the inaccuracies of all are a given. Rather, we are asked to take a side of either: (a) the priest, who sees untruthfulness as a weakness against impulse; or (b) the commoner, who simply recognizes the impulse without ascribing a normative value to it.

Notably, each of the actors in the underlying events place a certain degree of blame upon themselves. To be sure, certain character motivations are difficult to fathom from the modern Western moral and psychological perspective. To the 21st Century Westerner, an act like suicide is more likely to be associated with cowardice or mental illness than honor, and the idea of attaching shame to the victim of rape is abhorrent. Nonetheless, to the bandit, there is a certain sense of accomplishment in having killed a samurai in a fair fight; to the wife, there is a distinct appeal to the idea that women are uncontrollably emotional, and thus, not really consciously culpable; and to the husband, there is a higher degree of honor, courage, and meaning to death by his own hand than through an arbitrary accident – or worse, by being bested by a common thief. To be sure, there are common elements. (e.g., Why would both the bandit and the husband relay a story where the wife seems to have wanted to run off with the bandit? Perhaps the answer lies in the viewpoints of the common secondary narrator.) Even so, Kurosawa has something to say about humanity’s innate penchant for embellishment – the result of which is an inevitably obscured narrative.

Even when guilt is assumed by each individual narrator and even when each individual seems to have no rational reason to obscure those facts, each shows an uncanny inability to tell the whole truth. And even when vanquished, the ego refuses to give up the fight.

Richie sums up the whole proceeding as follows:

“In more ways than one, Rashōmon is like a vast distorting mirror or, better, a collection of prisms that reflect and refract reality. By showing us its various interpretations (perhaps the husband really loved the wife, was lost without her and hence felt he must kill himself; perhaps she really thought to save her husband by a show of affection for the bandit, and thus played the role of faithful wife; perhaps the woodcutter knows much more, perhaps he too entered the action – mirrors within mirrors, each intention bringing forth another, until the triangle fades into the distance) he has shown first that human beings are incapable of judging reality, much less truth, and, second, that they must continually deceive themselves if they are to remain true to the ideas of themselves that they have.”

(The Films of Akira Kurosawa (3d ed. 1996), p. 76.)

But Richie may be far too generous to humanity. Before there can be self-deception, there must first be deception. Absent a certain degree of mental illness, it takes far less time and effort to deliberately lie to another than it does for your ego to rewrite memories to the extent necessary to truly deceive oneself to the extent portrayed in Rashōmon. The testimony in the film is being presented only two days after the underlying events, and the differences between these stories cannot just be chalked up to spin. They are inconsistent on certain fundamental facts. As such, the film is not about our inability to perceive reality (or the relativity of perception, as Richie suggests), but rather our unwillingness to do so (or the relativity of truth). People are lying liars. And in the end (literally and thematically), Kurosawa presents a dialogue-filled narrative where the words mean nothing, but deeds are everything.

Grade: A+

Super essay on Rashomon, Steven! I’ve toyed with writing about it myself; I’ve watched it at least once or twice a year for the last few years with my college students, and I love it more each time. (Saw it on the big screen a couple of years back, too – so awesome.) It always provokes prolonged, impassioned discussion from my students, and it works perfectly in the context of my class, where we are not just discussing the form and structure of writing but also the meta-cognitive aspects of writing and thinking, viz. that our own biased perspectives are always shaping what it is we think (and write) and good writers are aware of their own perspectives and of the multiple perspectives of readers, too. Anyway, I don’t need to write an essay now that you’ve written such a fantastic one, and I’ll refer my students to yours, if you don’t mind! They get a bit muddled about who said what since we watch the film only once in class, and they have a difficult time grasping some of the essential themes and ideas, right off. (They get so distracted by trying to “figure out whodunnit”!) Discussion afterwards helps, but they could use a great essay like this to help them think through the details and implications of the film.

Thanks, Melissa, I’m glad you appreciated it. Unfortunately, it ended up being one of those things that sat on the shelf (or server) for a year waiting for me to complete the last bit. In any case, I would be honored for you to refer your students to it, as long as they make it through to the very last line 🙂