Spoiler Scale (How spoilery is this article on a scale of 1 to 10)? 8

Writer/director Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) is the single most disturbing film I have seen in the last decade. To be sure, I was not a big fan of the torture porn wave, although I have seen Saw (2004) and Hostel (2005). And although I have never covered my eyes in a movie theatre, there is a scene in Antichrist that I have never actually seen in my three viewings of the film. So consider this a warning.

Antichrist was extremely divisive when it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Von Trier is considered the provocateur of the art film world (at least in his own mind), and very rarely does von Trier create anything resembling a genre film (e.g., Dancer in the Dark (2000)). With Antichrist, von Trier has stated that he set out to make a horror film, but it evolved into something else. I would agree with the first half of that statement.

Von Trier’s scripts for his two most recent films, Antichrist and Melancholia (2011), were reportedly born from a long bout with depression and anxiety. It shows. In Antichrist, the two married characters (Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, the latter of whom won a Best Actress award at Cannes) have no names. (I will use capitalized pronouns to distinguish between them from here on out.) Their only child, a toddler, falls to his death from a window in the prologue – a beautiful black and white, super slo-mo, aria-scored six-minute piece of film (which should serve as a litmus test for whether the viewer will be able to swallow the rest of the film). As the film moves to a more realistic, handheld aesthetic, She is riddled with debilitating depression and panic attacks, and He decides She needs some isolated therapy. They venture out to a lone cabin deep within a thick forest where She had spent the previous summer with their child working on her thesis regarding the gynocide perpetrated on women throughout history. And bad things start to happen.

Like The Shining (1980), Antichrist is not so much a straight genre film as an exercise in genre – in this case, gothic horror cinema. And like Kubrick’s film, the genre conventions are merely a receptacle to inject what really terrifies us – imagery that taps directly into the subconscious. Whereas Kubrick used the slo-mo of waves of blood bursting from the elevator doors of the Overlook Hotel, von Trier provides a cascade of dead bodies whose hands emerge from a huge tree stump. And whereas Kubrick borrowed from Diane Arbus for the unsettling ghostly archetypes in The Shining …

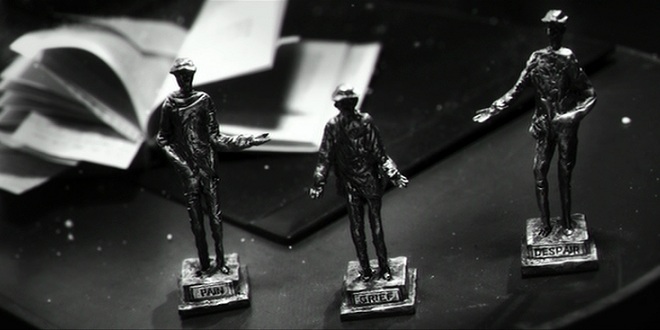

… von Trier conjures twisted visions of wildlife for the “three beggars” …

The choice of portraying the deer, the fox, and the raven in the way von Trier does adds very little to the plot and does nothing to explain the events in any logical sense. Rather, the interactions between He and the three beggars are intended to be nightmarish in a very abstract way. (The film is conspicuously dedicated to Andrei Tarkovsky, but von Trier indicates on the commentary to the DVD that the inspiration was primarily one of “mood.”) Beyond von Trier’s invocation of the subconscious, the rest of Antichrist is constructed from the bits and pieces we have seen before – from the instigating grief of the loss of a child in Don’t Look Now (1973) to the cabin in the haunted woods of The Evil Dead (1981) to the tortuous forced captivity of Misery (1990).

The most obvious touchstone is director William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). The connections are not merely visual, such as the flash frame of a demonic image in a reflective surface.

Rather, there are a number of narrative tropes common to both films. Both of the primary female characters undergo hypnotherapy. Both ultimately succumb to an externalized force serving as a loose metaphor for a psychological phenomenon. In the case of The Exorcist, Regan (Linda Blair) – inflicted by a barely budding sexuality – gradually evolves from a state of schizophrenia to demonic possession.

In Antichrist, She – whose personal anxiety over the loss of her child becomes existential – undergoes a secular possession by the pagan forces of nature haunting the woods of Eden. (“Nature is Satan’s church,” we are told.)

As for the male characters, Father Karrass (Jason Miller) in The Exorcist is a psychiatrist, and He is a therapist. More importantly, they are both rationalists, and as such, they are unable to cope with the supernatural forces that arise because they are handicapped by their nonbelief. (After all, there is no haunted house film without the willing skeptic to walk through the doors.) In the endgame, they both succumb to fear and aggression in a strikingly similar way.

But in that mêlée, anger gives way to compassion, as Father Karrass takes on the demon from Regan …

… and He takes on the existential anxiety of She.

But whereas Friedkin gives the viewer the sacrificial payoff necessitated by a certain sense of morality, von Trier is not so concerned with such things. After all, this is merely an exercise.

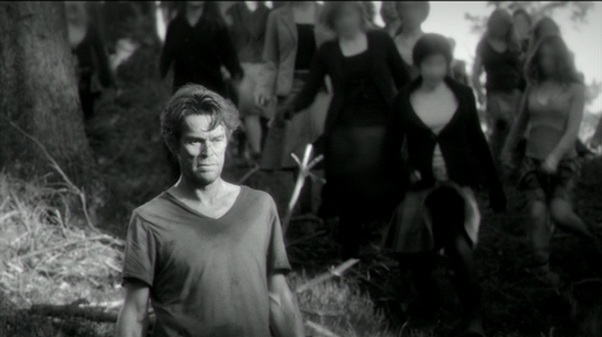

In the epilogue, having escaped from Her madness, He limps his way out of the woods. Along the way, he eats the berries – the sustenance of nature – as the ghosts of the three beggars look on, no longer tormenting him. But like the last survivor in the boat on that placid lake at the end of Friday the 13th (1980), He does not get away that easily. In the final scene that invokes the creeping black and white menace of George Romero’s zombies in Night of the Living Dead (1968), He eventually finds himself surrounded by hoards of faceless women converging upon him.

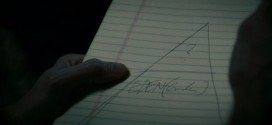

As if it was not already obvious from the symbol used for the “t” in the title card, the name of the cabin in the woods (“Eden”), or the scattered bits of curious dialogue (“a crying woman is a scheming woman”), the allegorical becomes literal. If Antichrist is an exercise in gothic horror, then the female gender is the Frankenstein’s monster.

The knee-jerk reaction by many critics was to simply dismiss the film as misogynistic. In the tradition of the classic films, which tend to spawn their monsters from the fears of things we do not understand, von Trier as a man may be simply expressing a fear of what he does not understand. Does that fear necessarily translate into hatred? Before answering that question, consider how fundamentally flawed the male character really is. What kind of therapist would undertake to treat his own wife for anxiety and depression from the loss of their child? Full of hubris and condescension toward his wife, He is clearly engaged in a kind of folly. And like many victims in this particular genre, He gets a certain comeuppance in the end. But of course, how von Trier portrays Him does not necessarily inform how von Trier feels about Her. All things considered, perhaps Antichrist could best be described as misanthropic.

In the final analysis, I believe von Trier succeeds – at least an academic sense. But unlike The Shining, Antichrist is a film that I can appreciate more than love.

Grade: B+

For the “She said …” on Antichrist, click here.