Spoiler Scale (How spoilery is this article on a scale of 1 to 10?): 9

This is Joseph Campbell territory. As such, it is important to remember that, as the cornerstones of a twentieth-century mythology, comic book characters are not supposed to be three-dimensional human beings, but more personifications of distinct ideas. Indeed, “personification” might be too strong a word. Rather, the best cinematic renderings of comic book legends imbue these characters with enough humanity to give the viewer an emotional entry point to the stories and a connection between those big ideas and their own world. In this sense, Bruce Wayne/Batman is probably the most accessible of all of the archetypes from the comic book universe. He is not an immortal moralist from another planet, but a psychologically fractured human being who manages to do what we all could aspire to – leverage our frailties and damages into something mighty and heroic.

As a fan of the 1970s comic books and the graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns, I was excited by Tim Burton’s interpretation, Batman (1989), and as a fan of Burton’s pre-CGI films, I was equally impressed with the sequel, Batman Returns (1992). That said, for better or for worse, Burton’s vision never let the viewer forget the comic-book sourcing. The unfortunate by-product of Burton’s commercial success was a slew of films (Dick Tracy (1990) through to Batman & Robin (1997)) that became increasingly steeped in the campiest mix of comic book and action movie conventions. In the case of the Batman films, the gravitas of the myth got lost in super-silly happy fun-time, much like the original TV show and accompanying Batman (1966). (The marriage of those distinct media would not be successfully realized until Sin City (2005).) Since then, I always thought the world deserved a truly cinematic Batman – farther afield from his original origins.

This brings us to 2005 and the arrival of writer/director Christopher Nolan, and his co-writers, brother Jonathan and comic movie alum, David Goyer. In retrospect, considering that much of the narrative magic of Nolan’s previous films (Following (1998), Memento (2000), Insomnia (2002)) relied heavily on tapping the psychological, Nolan seemed like an ideal filmmaker for the task. And from the first installment of his trilogy, Nolan was pegged with presenting the “realistic” portrayal of the legend. Of course, to Nolan’s detractors, any characterization of this particular genre of film tends to be absolute – that is, it must be either purely fun and entertaining (e.g., The Avengers (2012)) or it must be totally serious and realistic (i.e., an impossibility). But for me, the expectation was whether Nolan could pluck the myth from its comic book origins and present it in a natural way while never losing sight of the nature of the characters and the story. For the most part, Nolan’s trilogy strikes the balance between the myth and the humanity more successfully than any other comic book adaptation. And in its execution, Nolan recognizes that the pursuit of the principle idea behind Batman’s myth (justice) can be as philosophically fraught as Bruce’s psyche.

Batman Begins (2005) is easily distinguishable from the prior five film adaptations, and notable in its own right, for presenting an earnest origin story. Before accepting the role and making the requisite physical commitment (following his anorexic depiction of The Machinist (2004)), Christian Bale wanted an assurance that, unlike previous films, the title character would be at least as interesting as his enemies. And in this sense, the first half of this film is the strongest of the entire trilogy, and with its non-linear structure, the most representative of Nolan’s narrative style.

At the most obvious level, the story introduces a thematic cycle centered around fear – conquering fear and using fear as a weapon against those who would use it against others. But for Bruce, the first half of the film also portrays the end to a laborious and fruitless search to replace the irreplaceable, understand the source of what he sees as evil in the world, overcome his own guilt surrounding the loss of his parents, and take up his birthright as the protective benefactor of Gotham City. And throughout the trilogy, Batman’s battles are never personal – they are inextricably linked to the fate of all of Gotham. (The moral dilemmas posed by the Joker in The Dark Knight are shared with the citizens on the ferries in the finale, and by the end of the trilogy, Bruce must ultimately leave Gotham to live a normal life.)

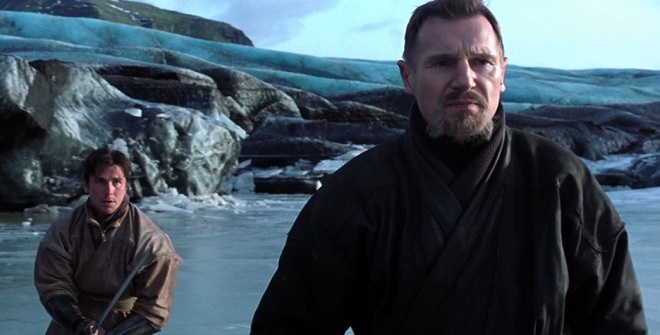

The first film also ushered in a cast that is outstanding from top to bottom. There is a certain weight added to the proceedings with the inclusion of regulars such as Michael Caine as Alfred and Morgan Freeman as Lucius Fox, who together serve as Bruce’s foundation (in more ways than one), and Gary Oldman as Detective/Lieutenant/Commissioner Gordon. And then there are the antagonists. In Nolan’s world, it is the prototypical mob boss, Carmine Falcone (the underappreciated Tom Wilkinson), who denies the young Bruce his vengeance and sets him on his journey of self-discovery. The most appropriate casting in the entire trilogy was Liam Neeson as Henri Ducard/Ra’s Al-Gul – a would be father-figure who resides on the dark side of the fence over which Bruce could have easily fallen – especially considering his prior take as iconic Jedi Master Qui-Gon Gin in the Star Wars prequels. That said, Dr. Crane/Scarecrow would definitely not be my first pick as a first Villain (with a capital “V”) to make an appearance (much less the only one to appear in all three films), but Cillian Murphy’s creepy, snarky take would prove that Nolan and company had clearly thought things through.

Despite the strengths of this first half and the casting, Batman Begins also manifests the weakest (and ultimately, the most inconsistent) parts of the trilogy. By the third act, this Nolan film starts to resemble a Burton film. Following an origin story of international scope, enhanced with the visuals of the glacier headquarters of the League of Shadows, we are suddenly thrust into the distinctly artificial sound stages of the Narrows just when the action gets going. In fact, the endgame bares little resemblance to the cityscapes of the next two films. And then there is the importance of maintaining the right narrative balance – being careful not to draw too much or too little from a comic book sensibility. In this sense, the scheme to destroy Gotham comes across as contrived – too on-the-nose with the predominant theme – to exist in the setting Nolan had created up to that point.

For the most part, The Dark Knight (2008) manages to sidestep most of these problems, as Nolan was able to leverage the success of the first film and use the streets of Chicago for most of his action set pieces. With the main character fully developed and with no particular need to provide any closure, the sequel proceeds with a straightforward, runaway freight-train of a plot that is mostly devoid of the narrative hallmarks of Nolan’s prior work. That said, there is more to this story than the continuing adventures of Batman. Set approximately six months after the events of the first film, Batman has Gotham’s criminals on the ropes. Bruce’s desire to become a symbol for Gotham buttresses the rise of the new idealistic D.A., Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), whose bravado offers Bruce hope that he might be able to hang up his cowl and take would-be love interest Rachel Dawes (the distractingly recast Maggie Gyllenhaal) up on her intimation that they might be together and live a normal life. But as anticipated in the epilogue of Batman Begins, the presence of Batman also results in “escalation.” In a world where a man dresses up like a bat to fight crime, misguided and ill-equipped vigilantes follow in his footsteps, and the organized criminal underground reluctantly adopts its own symbol to push back.

Much has already been written about Heath Ledger’s Oscar-winning performance as the Joker, widely regarded as Batman’s ultimate nemesis. But despite the Joker’s own representations as a mere anarchist, his existence is ultimately defined to be the unstoppable force to Batman’s immovable object. Paralleling the very nature of the Joker, Nolan and company tease the viewer with the possibility of – but ultimately eschew – any traditional form of character development. It takes no more than an hour of screen time to realize that the Joker’s stories about his scars are simply tailored to get under the skin of his particular audience. And by the time he coyly asks whether it looks like he has a plan, we already know who the ultimate “schemer” really is. For these reasons, while the Joker is the most unrealistic and random character of the entire trilogy on paper (considering the fate of anybody who chose to follow him), he is also the most convincing and compelling – the Mephistopheles seeking out souls, whose victory comes not in a mono-a-mono with Gotham’s dark knight, but in Dent’s tragic turn to the dark side.

In what is generally regarded as the best of the trilogy, The Dark Knight ends much like the second act of the original Star Wars series (The Empire Strikes Back (1980)) – on a resolutely somber note. The typical comic book adaptation would have ended with the Joker being outwitted and captured after a huge action sequence on the streets of Gotham an hour and twenty-five minutes into the film, tied up nicely with a neat little epilogue. But instead, the mayhem continues. The dual love interest is blown up in mid-sentence, and by the end of the film, the protagonists ultimately make the dubious trade of truth for hope. (Batman takes the blame for the crimes of Two-Face, with the complicity of Commissioner Gordon, to prevent all of Dent’s pending mass prosecutions of the mob from being overturned and give Gotham some hope; and Alfred burns the letter where Rachael would have chosen Dent over Bruce.) But as is evident from the Orwellian steps that Batman takes just to force a final confrontation with the Joker, the conclusion is just part of a more general ethical question that permeates the film (as well as the activities of the United States government in the War on Terror circa 2008) – What means are we willing to take to justify an end? Are we willing to become a monster to stop a monster? And for Nolan, it is the question that drives the film – not the answers.

In The Dark Knight Rises (2012), the chickens come home to roost eight years later. Crime is down in Gotham, thanks to the Dent Act that effectively turned Gotham’s prison into Guantanamo Bay. As a result, the people are complacent. The ruling class is smug. And a price has been paid. Hobbled by the injury suffered in the final confrontation with Two-Face and having become a fugitive from the law, Bruce retired the Batman persona and laid his fortune on the line to become an unmasked savior of Gotham (more like his father). But when he learned that the technology designed to develop an unlimited source of energy for Gotham (a cold fusion reactor) could be weaponized, he buried the project and retreated to the recesses of Wayne Manor like Howard Hughes – paternalistically unable to trust Gotham with that power. Meanwhile, Commissioner Gordon has lost the family he held so dearly and is scheduled to be replaced with the next election cycle, and at the beginning of the film, he is asked to make a speech on Harvey Dent Day and almost chooses to finally unburden himself of that lie.

Bruce is awoken from his malaise by a cat burglar, Selina Kyle (played convincingly by the tall Anne Hathaway), who not only steals his mother’s pearls, but his fingerprints. And bubbling up from the depths of Gotham’s sewers is a small army led by the mercenary Bane (a thankless role for a bulked-up Tom Hardy, whose 5’9” stature has obviously been enhanced through whatever tricks that enable Tom Cruise to be a convincing action star) – who seems visually designed to be the yin to Batman’s yang. At first blush, Bane seems to be assisting a competing industrialist (Ben Mendelsohn) intent on finally jettisoning Bruce from his own company. As the police seem unable to appreciate the gravity of the coming storm, Bruce suits up again – a decision that prompts Alfred to reveal the truth about Rachel’s ambivalent feelings toward Bruce and leave Bruce alone in his quest. Eventually, Selina – motivated by the promise of a new identity to make a fresh start – takes Batman to Bane, whose real goal is fulfill Ra’s Al-Gul’s destiny of destroying Gotham. And for the first time in the trilogy, Batman faces the inevitable – a villain who is able to overcome him physically in the most brutal mêlée of the entire trilogy. Batman is literally broken and condemned to a distant pit of a prison of Bane’s origin, where Bruce will be forced to watch Gotham on a big screen, while the hope of climbing out – a feat accomplished only by one – is dangled before him much like hope will be dangled in the faces of Gotham. With almost all of Gotham’s police lured into the sewers in a ruse that ends up trapping them underground, Bane realizes Bruce’s worst fears by appropriating the fusion device to serve as a bomb, and with the use of the very toys of Wayne Enterprises that empowered Batman, stages a violent coup to overtake Gotham in the guise of a populist uprising. In support of his faux cause, Bane reads the letter Commissioner Gordon had written about the true nature of Dent before releasing all of the prisoners of Gotham, while the citizens are led to believe that a random Gotham citizen holds the detonator to the bomb.

Nolan and company return to the machinations of Batman Begins by turning its theme upside down. Bruce’s mythological rise from the pit comes only from the realization that not all fears should be conquered – that he must embrace a fear of death to not only save Gotham, but to salvage his own identity and personhood apart from the Batman. And when Batman reappears in Gotham for the final battle, for the first time, he fights in the full light of day, and not alone, but with all of his allies of Gotham beside him – including Selina, Commissioner Gordon, and the only character whose own similar background allows him to intuit the true identity of Batman, Detective John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt, likable as always).

All that said, the primary weakness of The Dark Knight Returns is the sheer weight of the story. Like Revenge of the Sith (2005), there is a great deal compressed into a really long film, an apsect which often tends to have the effect of leaving the viewer with the impression that there should have been more. In this regard, Miranda Tate (Marion Cotillard) may be the one character too many. Actually, the concept of her character – and the ending that plays upon the audience’s assumptions about gender – is not as much of a problem as its execution. The ease with which she is able to become Bruce’s lover/confidant is jarring; and one cannot help but notice that every time she appears in the post-takeover Gotham, Bane’s henchmen seemed to show up, which made the ending not-so-surprising. But my issue with the character does not lie entirely with the script. (Cotillard’s death scene is worthy of derision.)

Notably, the last installment generated allegations of Nolan and company peddling in half-baked political statements. But why does the use of imagery from 9/11, financial collapse, etc. somehow necessitate the advancement of some particular viewpoint? Such assertions of partisanship – and the fact that they come from both the Left (e.g., David Sirota, “Batman Hates the 99 Percent,” salon.com (7/18/2012)) and the Right (e.g., Rush Limbaugh, “The Batman Campaign” (7/17/2012)) – seem to say more about the critic than the efficacy of the film in terms of realizing the filmmakers’ intent. Nolan’s trilogy merely mirrors our own anxieties with a degree of specificity that hits close to home, thereby fostering a closer connection between the audience and the mythology. And within such a familiar backdrop, there is a common thread that runs deeply through the major villains in all three films – from Ra’s Al-Gul’s “purging fire” speech, to the Joker’s dialogue with Batman about being ahead of the curve, right on through Bane’s populist appeal to the proverbial 99% – that is, a cynicism about the nature of society, and particularly, whether society can fulfill the pursuit of justice even when the machine of justice has itself has metastasized into an impediment. All that said, in the dark world Nolan has created, there are difficult questions presented without providing any easy resolutions, and perhaps that is part of the reason why somewhat greater masses flocked to viewings of The Avengers in the summer of 2012.

As I look back at all of these films, I am amazed at how different each one feels – not merely three episodes in a comic book franchise. To be sure, the trilogy is not perfect. Nolan and company have clearly opted to define the characters by what they do (to quote a line repeated in the first installment) in relatively complicated plots, which ends up burdening the dialogue with exposition and thematic touchstones – some of which are unnecessarily repeated within the same film (e.g., “You either die a hero or live long enough to be the villain”) or across multiple films (e.g., “There’s a storm coming”). But on balance, in a blockbuster market filled with films from the likes of Michael Bay and Paul W.S. Anderson, Nolan has created a set of films that represent cinematic, layered, and accessible myth-building at its best.

Grades:

Batman Begins (2005): B+

The Dark Knight (2008): A

The Dark Knight Rises (2012): A-